Sometimes only a fleeting spell in Todmorden is enough to draw someone back later, in the hopes of a better life. Thanks to Leesa Harwood for sending us this story about her ancestors!

The gravestone in Christ Church Graveyard marks the burial place of Charles Neesham, his wife Jane (Kilburn) Neesham and their daughter Margaret Eleanor (Neesham) Barker.

Charles Neesham was born in Evenwood, County Durham to John and Elizabeth Neesham. His father John was a pitman, most likely working at the Randolph coal mine in the town. By the time Charles was 10 his family had moved 30 miles southwest to Muker, in Richmond North Yorkshire. Charles’ father now worked as a lead miner in one of the many smelting and lead mines in Swaledale. It was a hard life, and the demise of the lead mine had already started by the time John moved his family to the Yorkshire lead mines. By 1871 there were few jobs and miners started to migrate out of Muker as the lead mining industry collapsed.

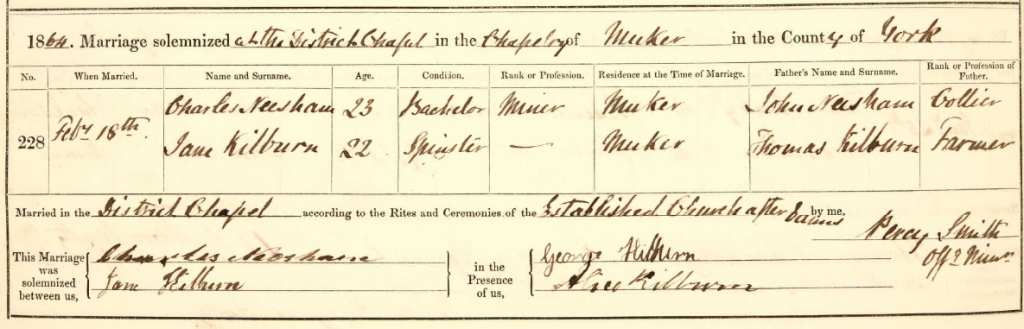

Charles went back to County Durham with his wife Jane, who he had married in Muker in 1864, and by 1871 they had 4 children. Charles was a coal miner at Shildon. Shildon was at the centre of the railway revolution (the first passenger train had begun its journey in Shildon in 1825 on the Stockton to Darlington railway line) and coal was key to moving and being moved around by the steam engines. So, whilst mining was still dangerous and unregulated, (low paid) jobs were plentiful underground.

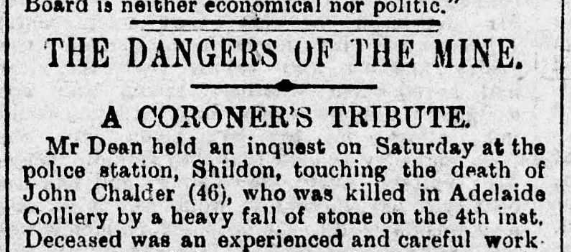

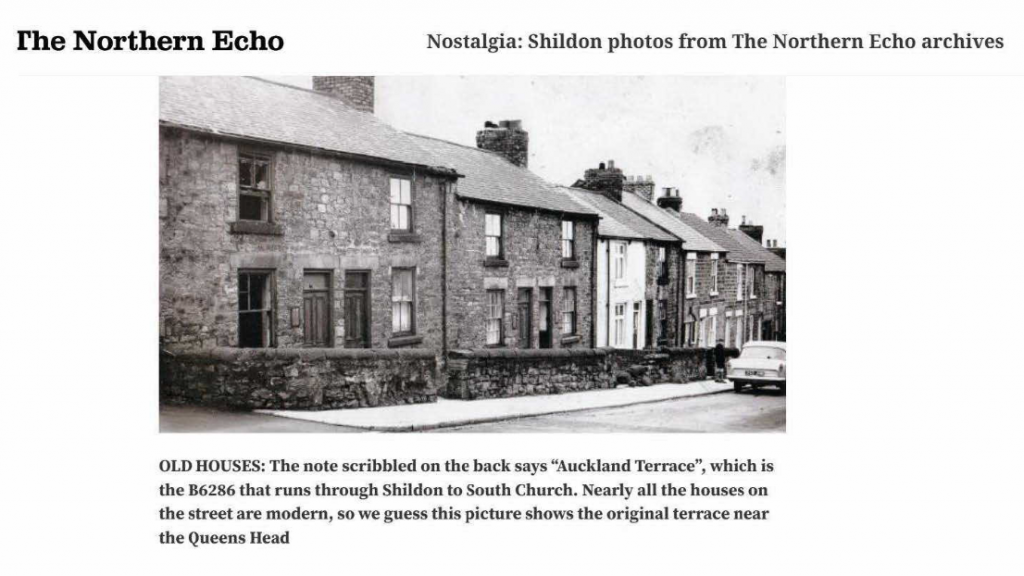

By 1881 Charles was living at Aukland Terrace, a line of workers’ cottages in Shildon, with his wife and 3 youngest daughters. Charles was working as a miner at the Adelaide Mine, which would soon make headlines for tragic reasons. The Darlington North Star newspaper reported on the fatal collapse in the mine, and the lucky escape of Charles Neesham:

THE DANGER OF THE MINE – A CORONER’S TRIBUTE

Mr Dean held an inquest on Saturday at the police station, in Shildon touching the death of John Chalder (46), who was killed in Adelaide Colliery by a heavy fall of stone on the 4th inst. Deceased was a careful and experienced workman, and had been employed 20 years at the colliery. The evidence of Charles Neesham who was working along with the deceased shoed that the former, upon returning to where Chalder was working discovered an obstruction in the way of his tub. He called out several times to Chalder but no answer came and upon the approach of John Blekin, master shifter, they made their way to the other end of the fall, and then perceived that their unfortunate, fellow workman was entirely covered by the fall, which was several tons in weight. Neesham declared that they had perceived nothing unusual in the roof, and a very short time previously deceased and he sat under the fatal spot and had their bait. Witness was much affected by the sad occurrence and was unable to stay to assist in extricating the mangled remains. The master shifter said the men were employed three hours and a half in removing the mass which covered the deceased. The stone above kept falling in small pieces whilst the men were at work and they had to stand and reach over to clear the debris, so dangerous was the place. At the conclusion of the evidence the coroner feelingly remarked:

“This case only confirms my impression of some years past, and when I meet a miner going to his daily labours with the safety lamp in one hand and his life in the other, I feel that I ought to take off my hat to him as a better man than I am. This case but shows that these poor fellows in working in the mine, stand in jeopardy during every hour of their toil”.

Evidence to the timbering of the place was also tendered and a verdict of ‘Accidentally killed’ was returned. Mr Plummer, Assistant Government Inspector of Mines was present during the inquiry, and Mr Bigland the colliery manager.

Somehow Charles Neesham went back to work in the mine. In 1891 he is recorded as being a coal miner in the same town and probably the same mine.

Let’s turn our attention to Jane Neesham, Charles’ wife. Jane was born in 1841 in Muker, Yorkshire. She would have met Charles when he lived with his parents in Muker sometime after 1851. In 1861 before she met Charles, she had briefly lived and worked in Portsmouth, Todmorden as a dressmaker before moving back to Muker and marrying Charles in 1864. It is likely that when they moved west, away from County Durham, Jane’s previous knowledge of Todmorden was the driving force behind returning with her husband and two youngest daughters. It’s also possible that her sister Alice, who had married a joiner named William Milner Butson and moved to this area in the 1870s, and who died at Greenhurst Hey in 1896 (and is buried here at 21.40), kept the area alive in her thoughts.

The reason for their move is unknown, but they had lost 4 of their 6 youngest children whilst in Bishop Auckland. Three of their children died aged 1, 4 and 5 respectively from scarlet fever and one (Elizabeth) aged 23 from post-partum infection. As well as bringing their youngest daughters (Margaret Eleanor and Jane) they also brought Elizabeth’s 8-year-old son Charles with them to Todmorden, no doubt hoping for a healthier life in their new home.

In 1902, Charles and Jane’s daughter Margaret Eleanor married a Todmorden lad, Peter Barker and moved to Littleborough where he owned a Grocers and Confectioners. Charles and Jane’s youngest daughter Jane also lived with Margaret and Peter, as well as Charles (now 18-years old and assisting Peter in the shop). Charles lived long enough to see his daughter married and settled. He died in 1905, aged 60 of tuberculosis of the bones.

Charles’ wife Jane outlived her husband and daughter Margaret Eleanor (who died in childbirth in 1914). Once widowed, Jane went to live with her youngest daughter, husband and granddaughter, then in 1921 with her son-in-law Peter Barker and her 3 grandchildren at Peter’s bakery in Littleborough. She died in 1924 aged 82.

More of Charles and Jane’s children are buried at Christ Church and we look forward to hearing more about them in the future! Margaret Eleanor especially, since she’s buried here too. She has her own story – a sad one – and we’ll leave it for Leesa to tell it.