More continuity here for those with an interest in the Freemason’s and later Weaver’s Arms on Blind Lane – maybe you remember William and Martha Jane Sutcliffe under the school’s story? Well this is how they got there (or at least how Martha Jane got there).

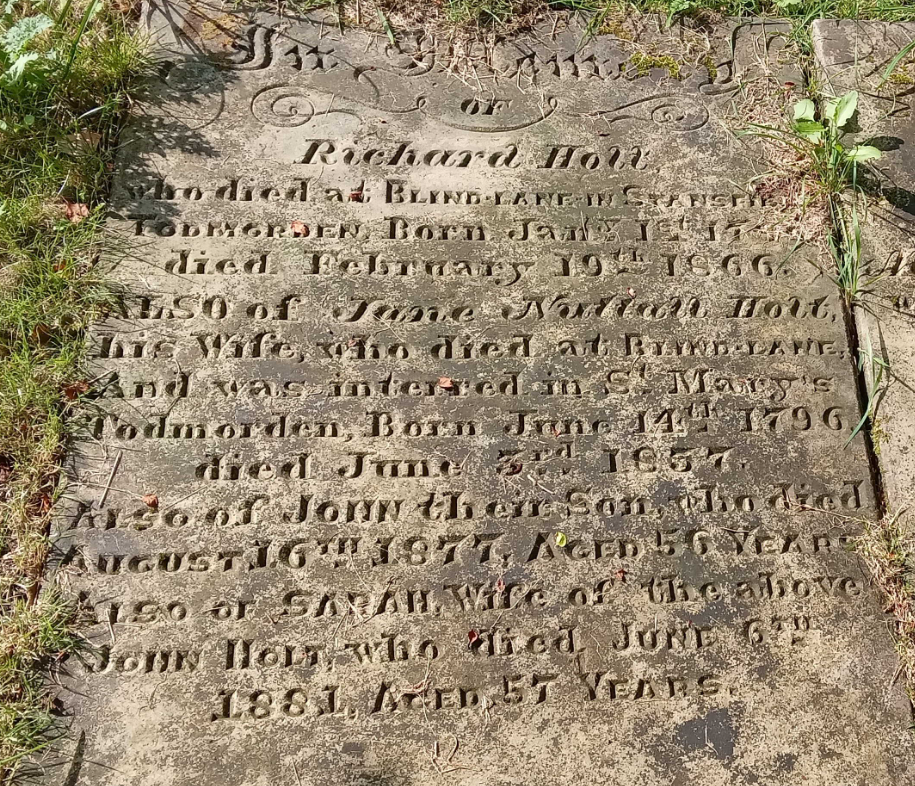

We have go back a bit though. Let’s start in 1796 when our first two protagonists were born, Richard Holt in Stansfield and Jinney (later Jane) Nuttall in Todmorden. Richard’s parentage and baptism are untraceable but Jinney’s parents Thomas and Mary (Crabtree) Nuttall were weavers who would eventually end up living at Kilnhurst. Jinney was the youngest of their seven children. She and Richard were married at St. Mary’s in January 1821, just a month before their son John was born, with four more children following between then and 1836. Only one would die an infant, too – James, who died aged two in 1828 and was also buried at St. Mary’s.

Jinney’s death in 1837 hit Richard hard at first but he rebounded because he simply had to: he was busy running a lodging house on Blind Lane which took in both travellers and the poor, serving as a halfway house rather than a full-on workhouse. Its reputation at the time is hard to discern but there are cases here and there hitting the Rochdale or Halifax papers of people being apprehended there who were a bit on the dodgy side. Richard never remarried and this meant that his children were lodged elsewhere – where, we don’t know. Jinney went into her family’s grave.

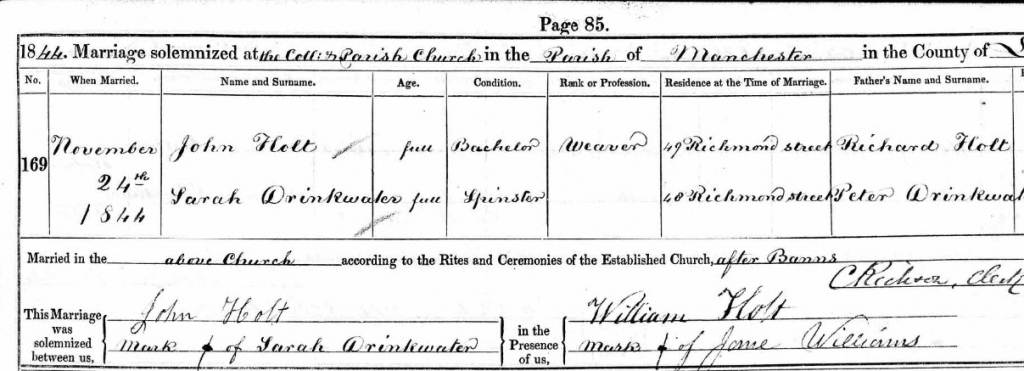

Richard expanded his business interests into running the Freemason’s Arms, now replaced by a red brick building which is private apartments, and over time made quite a bit of money doing so. His children grew up and moved out with John in particular moving all the way out to Manchester. There he met Sarah Drinkwater, the daughter of cotton spinners Peter and Martha, whose family had originated in Warrington but moved to the city for work. When they married in 1844 their addresses were 48 and 49 Richmond Street; they literally lived across the road from each other. The couple moved to Pilkington, taking the now-widowed Peter with them, and there their two children would be born – Martha Jane in 1850 and Joseph in 1853.

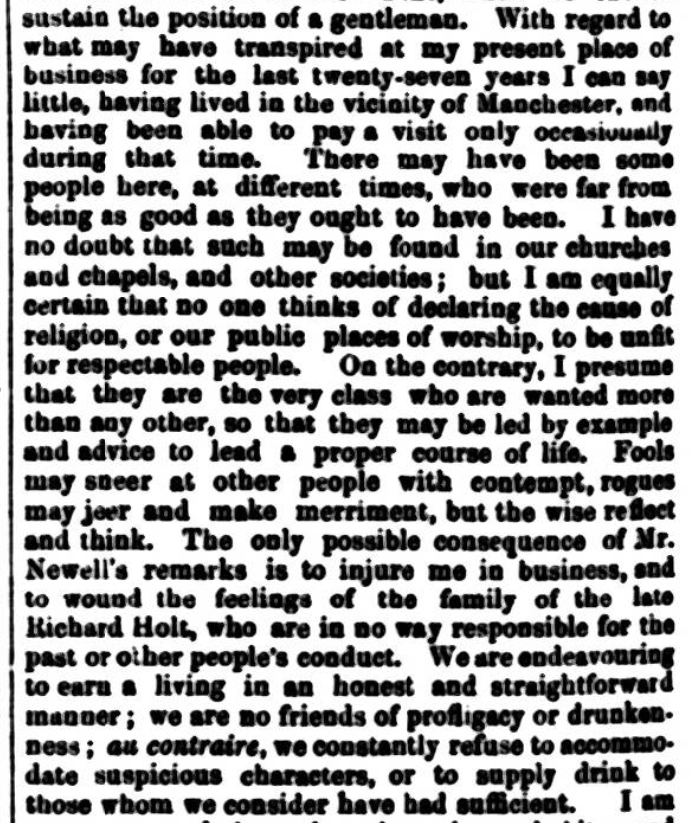

Meanwhile Richard continued to manage the Freemason’s and then the Weaver’s Arms. John, Sarah and family returned from Pilkington around 1864 presumably to assist due to Richard’s health or age. In February 1866 he died, and John – the dutiful eldest son – took over the family business. The family business was more than just the lodging house though; it was also their good name. Just shy of a year later at an animated meeting of the Board of Guardians to discuss the building of a new workhouse, Board member William Newell had a few words to say about lodgings for the poor in the district:

“Some persons who applied they could not admit, and how did they perform their moral duty to such as these – where sent they them? – they sent them to the lodging-houses at Blind Lane – Dick Holt’s – one of the very lowest places in the neighbourhood.”

Whatever Richard’s failings as a proprietor might have been, John couldn’t see them (or didn’t wish to admit them) and a strongly worded letter from him followed to the Todmorden Advertiser. When a letter’s opening sentence reads “Will you kindly allow me, through the medium of your journal, to tell Mr. Newell that I pity him as a cowardly slanderer for his remarks with regard to my late lamented father, and the neighbourhood in which he once lived” you know the writer is about to deliver the goods. “Better would it have been had he remained in the ranks, when he cannot sustain the position of a gentleman” indeed!

John ended his letter by putting his money where his mouth was, and ending the agreement he had with the Board of Guardians to take on overspill from the existing workhouses. After all, if his house and his neighbourhood were so terrible, why would the Board want to send anyone there in the first place? Touché.

But now…let’s think of another hypothesis. So much writing about the past necessarily has to veer off into fiction, or at least, creative interpretations of the facts. And there are a few facts we’ve left out that might change how you view John’s return from Pilkington and his aggressive defense of his father and the family name.

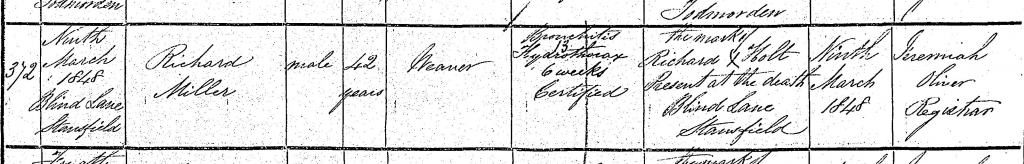

Let’s go back to Richard’s life after Jinney died. He never remarried, this is true. His home covered numbers 7, 9 and 11 Blind Lane and in 1851 there was a total of 34 lodgers alongside Richard and young Richard Jr., the only child of his and Jinney’s to still be living with him at any census return. One of those 34 lodgers was widow Bridget (Ledden) Miller – sometimes in the newspapers as Mellor – and her four children, Ann, Mary, Elizabeth and Louisa. There’s a secret here though, and one which was poorly kept at the time: Elizabeth, maybe, and Louisa, definitely, were Richard’s daughters with Bridget. The issue is complicated by Bridget’s late husband also being named Richard, but mathematically it’s possible for Elizabeth to be his daughter. Richard Miller died on March 9th 1848, and Elizabeth was born on December 11th 1848. Richard’s cause of death was bronchitis (13 weeks) and hydrothorax (6 weeks), so we leave the question with you, the reader, as to whether or not it sounds likely that one of the last things Richard Miller ever did was impregnate his wife…

Richard Holt being the informant at his soon-to-be-mistress’s husband’s death is a nice twist that you’d roll your eyes at in a fictional tale.

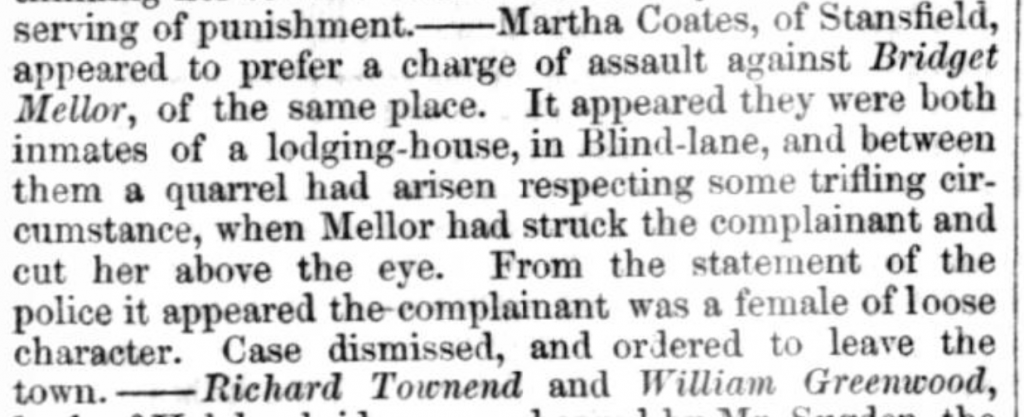

Richard and Bridget had…maybe…three children together altogether. Elizabeth came in 1848, then Louisa in 1850, and finally Joseph in 1853. John’s feelings about having a half-brother with the same name, and a year younger, than his own son, are not on record. Bridget’s status in the house is obscured in most records – she is described as a servant in 1851 and 1861, and on the occasions she appears in the newspaper (either for getting into an argument with a neighbour or for having a shawl stolen) no mention is made of her real relationship to Richard. In fact, in the latter case, the case against Bridget is thrown out because her accuser is deemed to be a woman of “loose character”!

He had enough influence, it would seem, to avoid the scandal.

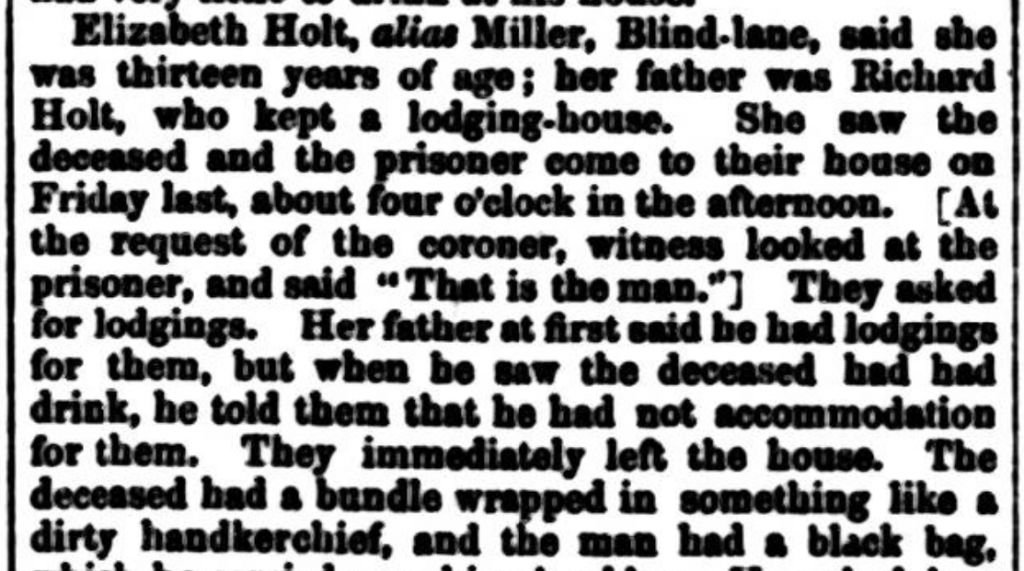

Elizabeth’s baptism, and birth registration, is as the daughter of “Richard and Bridget Millar” but Louisa’s baptism record plainly states that she’s the daughter of Richard Holt, lodging-house keeper, and Bridget Miller. And even when Elizabeth appears as a witness in the case against vagrant Joseph Leach, supposed to be the murderer of an unknown woman found in the canal, her name is given as “Elizabeth Holt, alias Miller”, and she testifies to being Richard’s daughter.

Now this – three (that we know of) illegitimate children – may have been another good reason for John to guard the family reputation, and also might be one of the reasons Newell denigrated Richard. And the influence Richard held which meant he and Bridget could live so freely together for long may have explained Newell waiting for him to be dead before speaking up.

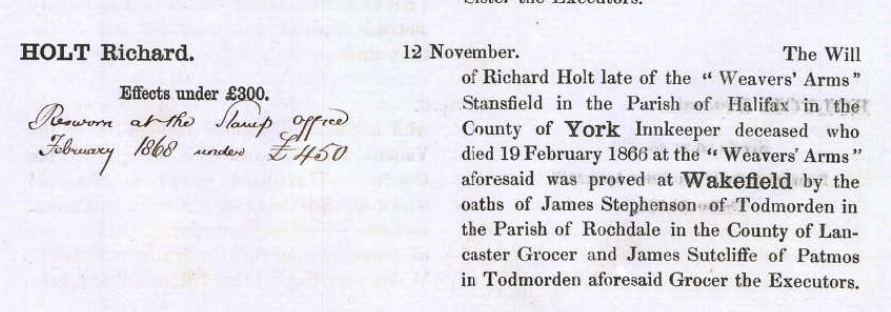

There’s also one final wrinkle to Richard’s tale that we didn’t cover yet. He died in February 1866 – his will was proved in November of the same year – but it was resworn, and for a higher amount, in February 1868. Was there a dispute over money, the will, a codicil, some sort of extra layer of complexity due to his second family? If there was we can’t find the details of a dispute. There may not have even been one. Poor Bridget had lost her daughter Ann in 1854, Louisa in 1855 and Mary in 1861; they were all buried up at Cross Stone with Richard Miller, conveniently distanced from Jinny and St. Mary’s! She and Elizabeth disappeared after Richard’s death with only Joseph sticking around to lodge with an unrelated family on Dale Street. Bridget might have simply had enough of Todmorden after her partner’s death and chosen to go of her own volition.

Back, now, to John and Sarah. They and the children took over at the Weavers and continued to run a lodging house alongside the pub, although significantly reduced in scale. The 1871 Census enumeration for the properties was handed to John to fill out and curiously…insensitively?…he described Sarah as a “lunatic” in the margins. Cheers! Now, thanks to John sacking off the Board of Guardians, there were only seven lodgers to account for. The Holts continued to get mentions in the newspapers whenever there was trouble at or adjacent to their pub and house but generally life seems to have gone fairly smoothly for them both.

John died in 1877, not long after handing the license over to William Sutcliffe, his son in law. Sarah continued to live at the pub with her William and Martha Jane and their children but her own time came in 1881, and she was buried here with her husband and father in law.

Pingback:S3.5 – William and Martha Jane Sutcliffe – F.O.C.C.T.