This is one of our mysteries of the graveyard, and a tale about the power of grief and shame. Caroline Coles was not a poor woman, and her husband not without some local prestige; so where’s her grave, and where are her two children who are buried here? They might be at this plot marker here, H. C. at 38.11, but we have no way to be sure.

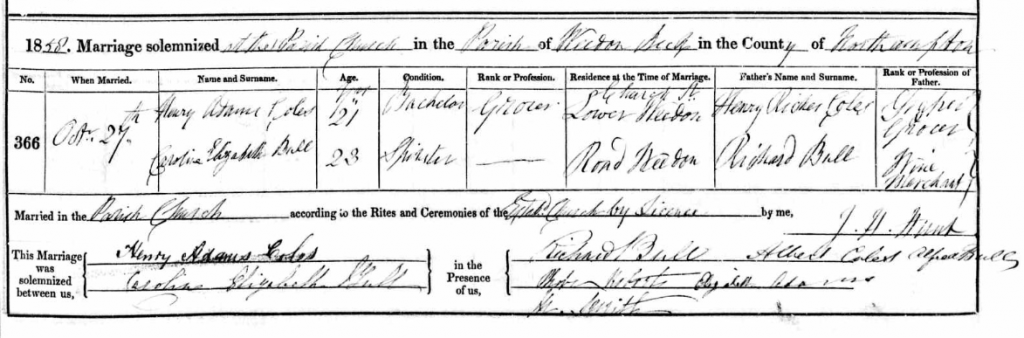

Caroline Elizabeth Bull was born in 1836 in Burton-on-Trent, Staffordshire. Her father Richard was a wine and spirits merchant, brewer, and horse dealer, and a very well off one at that. He and his wife Elizabeth were travellers during their marriage as you can see from their childrens’ birthplaces on the census returns; Southwark in London (Elizabeth’s home), then Burton, then Branston, then Birmingham. He was a Leicester lad but Weedon Bec near Northampton was where he eventually settled after Elizabeth’s death. Caroline grew up in a villa, with a servant, and still in school at an age where the majority of the people buried here at Christ Church would have been full-timers in the weaving or spinning mills. She wasn’t in the elite but she was more than comfortable, and she would have been expected to marry comfortably if the time came. The time did come in October 1858 when she married Henry Adams Coles.

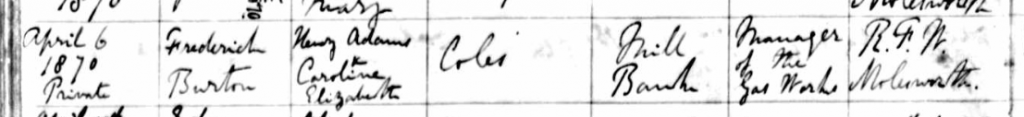

Now, Henry, he was a young man on the rise. He had taken on his father Henry Richer Coles’s grocery and draperies business along with his brother Albert, and it’s no surprise that one young businessman and one older businessman were in the same social circles. Caroline threw herself into his business, her occupation on the 1861 Census given as “grocer and draper’s assistant”, and also threw herself into raising their family. Both Bulls and Coles had a taste for names and so Caroline Eliena (after Henry’s mother), Edward Albert, Fanny Elizabeth, Harriet Susannah, Beatrice Margaret, Frederick Burton, Robert Eimer, and Laura Eliena Coles were born. Richard Bull died in 1864 and his estate of under £2000 was settled with presumably some money going to Caroline, and the following year is the last year we find Henry Coles living in Weedon Bec. The Coles had moved to Tranmere in Cheshire by 1869, when Beatrice was born, although they made sure to baptise her in Northampton too. And by 1870, when Frederick was born, the Coles were here in Todmorden.

Henry had been taken on as the manager and secretary for the Gas Works at Millwood, a big jump away from groceries and draperies, and the family were living at a nice home at Ridge Bank overlooking Cobden, with a young servant they brought with them from Weedon Bec. Money couldn’t buy you everything though and Frederick’s baptism being labelled as “private” is a clue that not all was well. Private baptisms were often done in haste when a baby was born alive but with serious difficulties. Mary Jane Bell died only four hours after she was born but her parents managed to effect a private baptism for her. Whatever Frederick’s difficulties were he was able to hold on until June 1870, when he died and was buried somewhere here at Christ Church.

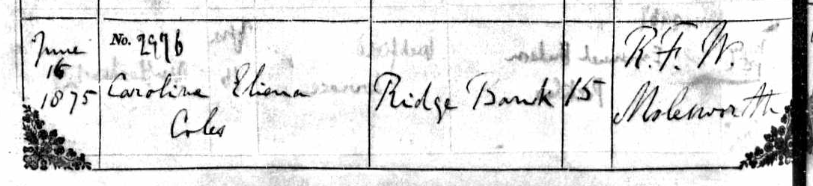

The family had another loss in 1875 when Caroline, their firstborn, died at only 15 years old due to meningitis. Again, she was buried here, presumably with her brother since the Coles wouldn’t have been having their children put into pauper’s graves…which is why when Laura, their last child, was born, she was given the middle name Eliena. The original child who carried it was gone.

Two deaths for eight children was not great but still not that far above the national average, and so the Coles continued on. Henry stayed at the Gas Works and is almost certainly somewhere in this photograph of gassy gentlemen from the 1870s (courtesy of the TAS). He would have been in his 30s at this point, maybe even 40. Which one is he?

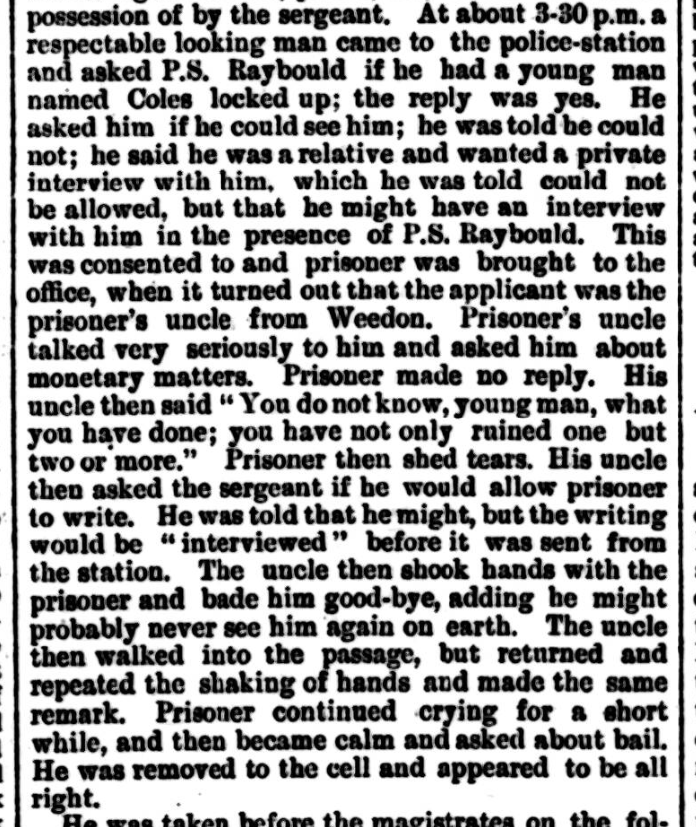

While Henry worked, Caroline worked in her own way, getting involved with the Sunday School at Christ Church along with the other well to do ladies of the town. But this story is not about a family’s success, it’s about why this successful family is in an unmarked grave, and 1882 is the annus horribilis and turning point. In 1882 the family was still at Ridge Bank but another child was missing – Edward Albert, the eldest son, had headed to Halesowen near Birmingham to work as a commission agent. He was a bright young man and personable, having been a regular at Christ Church’s Sunday School and choir and football team. But life away from home, with who knows what sorts of influences around him, led him to make a very foolish decision. He defrauded a butcher named Moseley of £4 9s and sixpence, the modern equivalent of £450, and lacked the finesse to get away with it. A warrant was issued for his arrest and he was taken into custody at Halesowen. He had two visitors during the first 24 hours of his incarceration; a friend, who brought him food and beer, and one of his uncles, who decided that the best way to drive home the meaning of Edward’s crime would be to crush his spirit utterly.

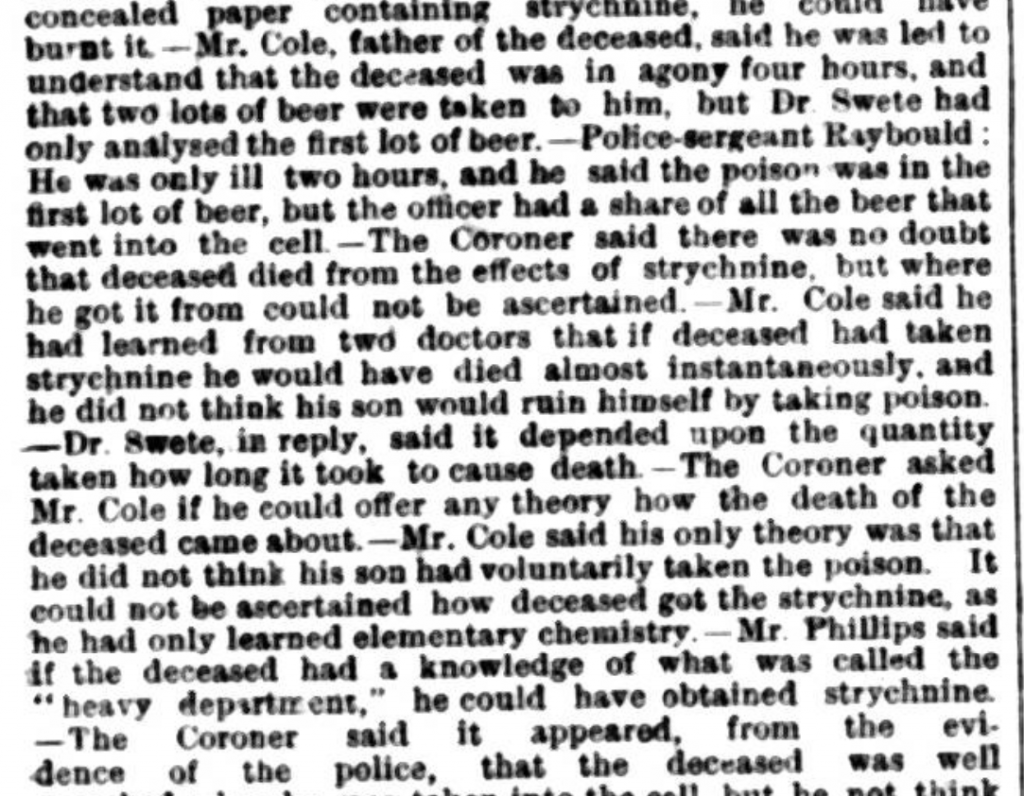

“He might probably never see him again on earth” was meant to be a sign that this uncle was disowning Edward, and likewise the accusation that more than only he would have been ruined by his actions was meant to remind him that his parents would have to make up the missing money if it was gone…but they took on a different, painful meaning as time passed. First, there was the short passage of time. Edward wept, slept, and the next day seemed well enough. But then at dinnertime the guard heard a cry for help, and found Edward on the floor having a seizure. He had taken strychnine, and within two hours was dead.

The inquest was covered widely and had to be carried out in two parts because Edward’s stomach contents needed testing. Henry attended and at first swore that his son “died of a broken heart”, and later repeatedly asserted that Edward would never had done this, that he barely knew chemistry and wouldn’t know where to get strychnine let alone carry it on his person so he could escape justice. He struggled to accept the reality of the situation. But how could he? Edward’s death was ruled a suicide but with no determination as to who provided the poison (the friend who brought the beer? His uncle? Himself?). He is buried at Halesowen, on his own in an unmarked grave. Not in Todmorden.

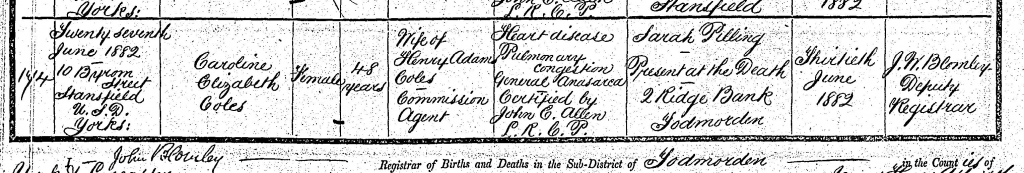

Henry returned home and five months later he saw a death from a true broken heart: Caroline’s. She died in June from heart failure at the age of 48. She’s the last Coles into the curiously unmarked grave here at Christ Church.

How does a family recover from such a painful incident? The Coles began to disintegrate at this point. Henry immediately disappears from all adverts and notices regarding the Gas Works – a new manager’s name was on everything before the inquest had even been held. Harriet left for London soon after and became a dressmaker, supporting herself independently. Beatrice moved to Andover to live with her uncle, the Rev. Eimer Coles, as his housekeeper. Robert and Laura went back to Northampton to be supported by relatives. Fanny had already moved back to Weedon Bec to live with her grandparents, but after the double bereavement she came back north and stayed at her father’s side while he either worked to repay Edward’s debt or was unable to.

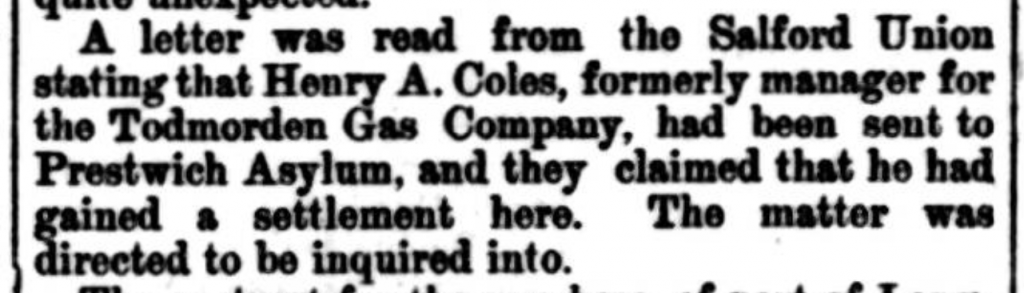

He and Fanny went back to Weedon Bec at first and in 1886 he ended up in Berrywood Asylum there for a short time. He left and went back north with Fanny but again, in 1889, he ended up at Prestwich Asylum for a month. The Todmorden Board of Guardians paid a little towards his costs at the second place, probably out of sympathy.

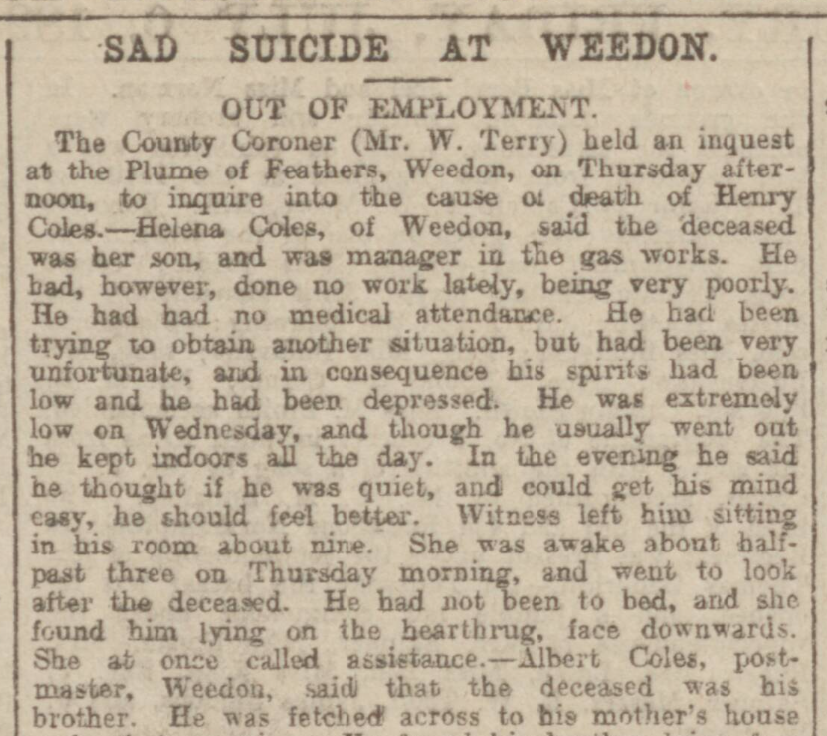

1891 saw Henry and Fanny living in Tal-y-sarn, Wales, and Henry back at work as a gas works manager. But in 1891 his youngest son Robert, who was working as a butcher’s apprentice back in Weedon Bec, died. Henry and Fanny headed back there. But Fanny had met a young man and ended up going back to Caernarvon to get married in 1893. Henry was alone, again, and being back in Weedon Bec wasn’t enough to calm his mind. He was working but soon found himself out of work and struggled to find employment again. His mood dipped even further if such a thing is comprehensible. In July 1894, he took his own life by cutting his throat with a razor.

….but he isn’t buried in Todmorden either. He’s buried at Weedon Bec, also in an unmarked grave. It took six years for probate to go through and after everything, all he had to pass on to his children was £66. Edward’s uncle’s prediction had come true. “Not only one, but two or more” had indeed been ruined.

The Coles clearly felt Todmorden was their forever home – why else bury two children there, when there was a family vault in Weedon Bec? They were clearly devastated by Edward’s and then Caroline’s death – why else did it all fall apart, why else did Henry lose his sanity not once but three times, why else did a gravestone never materialise? And they clearly, in matters of death, could not control things – why else would Edward not be brought back to Todmorden or Weedon Bec, why were Robert and Henry not taken back north? Other family must have intervened.

That’s how Frederick and the two Carolines ended up without a proper stone, despite their class and status.

There is a chance that the plot marker at the beginning of this post belongs to the Coles, but this is based mainly on the initials and the star emblem looking identical to another plot marker, that of Thomas Taylor at 37.23 who was buried in 1869. However, most plot markers for someone who used their middle initial include the middle initial, notably G. S. M. and M. A. T. who are either side of H. C. – so why does it not say H. A. C. if it’s Henry’s? That’s why we cannot be very sure at all about who H. C. refers to, not wholly. You want it to be Henry Adams Coles but wanting doesn’t make up for the lack of certainty.